Total Freedom

Patrik Schumacher, the director of Zaha Hadid Architects, on his ideological evolution, unleashing parametric urbanism, and the politicisation of architecture

interview by Martti Kalliala

Most architects active in the public sphere would probably place themselves on an ideological spectrum ranging left to right from [prefix]-Marxist, to fuzzy liberal, to neoliberal — generally with a diminishing interest in being vocal about one’s position when moving rightwards. Patrik Schumacher, director of Zaha Hadid Architects, founder of the Design Research Laboratory at the Architectural Association, and a leading thinker and practitioner of parametric architecture, is, however, a contrarian. His views on the primacy of the market as the essential organising principle of society are so far to the right that he in fact resides outside, or ‘above’ the spectrum as libertarians and anarcho-capitalists tend to illustrate their position. While this position is typical for much of Silicon Valley’s tech elite, it is an anomaly within architecture.

And Schumacher doesn’t shy away from expressing it, hammering away Facebook posts and blog comments in the multiple-thousand-word range, expounding a politics and idea of architecture’s essential social task based on a framework provided by the Austrian School of economics and the work of Niklas Luhmann.

Indeed, it is my impression that it is in fact Schumacher’s prolific online presence rather than his monumental work in the form of the books Parametricism I and II (or the recently published anthology, Politics of Parametricism) which has in recent years spawned a curiosity towards his thinking amongst those who have previously either had little interest or had an aversion towards the particular design language he employs.

I was curious to hear Schumacher elaborate on some of the public positions he has taken lately, from his surprising involvement with the newly-founded libertarian micro-state, Liberland, to his takedown of ‘PC culture’ in contemporary architectural circles, to the general evolution of his own thinking.

This interview was conducted a couple of weeks before the unexpected death of Zaha Hadid.

MK — In a recent lecture, aptly named ‘In Defence of Capitalism’, you talk about your personal shift from a self-proclaimed ‘revolutionary communist’ to an advocate of libertarianism and anarcho-capitalism. Could you tell me more about this ideological turn; what triggered it?

PS — How society works or should work is the most momentous question that I feel confronted by, but it’s also the most complex, non-trivial, perplexing question. I started early on to invest a large chunk of my learning and energy in the attempt to penetrate the matter and reach a position I can argue and commit to, and to break into the circle of those who address and claim to answer the deepest questions. What is the world? What is thinking? How is knowledge possible? These questions led via language and life forms (Wittgenstein) to society (Habermas) and political economy (Marx). Thus I arrived at Marxism first via theoretical philosophy rather than any prior political bias. Wittgenstein, Habermas and Marx showed that pure philosophy was vain. Habermas and Marx showed that the theory of society must become the fulcrum of all philosophy. Marx showed that theory must fuse with practice. He delivered a system of political economy as a crucial theoretical component of a radical, transformative political project. Marx’s philosophy is of a totalising scope and able to theorise its own historico-sociological conditions of emergence and development. Marx’s system was the first ‘super-theory’ in Luhmann’s sense, i.e. a theory that is able to fully and consistently theorise itself.

Marxism seemed most profound and ambitious to me. Nothing else came even close. Marx’s analysis of capitalism’s anarchy, implying that the aggregate result of atomised human action confronts everybody as alien force, and that communism offers the prospect of an emancipated mankind finally gaining self-conscious control over its own destiny, seemed as compelling as it was inspirational, underpinning my activism.

My architectural position during my Marxist years was initially independent of my understanding of political economy. In the mid-1980s, at Stuttgart University’s architecture school, I had discovered a new fascinating degree of freedom and compositional complexity in the work of ‘deconstructivists’ Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry, Coop Himmelb(l)au, amongst others. In 1987 I moved to London to continue my studies and made two further discoveries: Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaux and the ‘rhizome’, and Marxism Today’s post-Fordism discourse. For the next few years I invested my time in these three discoveries (whilst in 1988 I joined the studio of Zaha Hadid).

In the early 1990s these three strands fused in a synergetic combustion when I realised that Deleuze and Guattari’s philosophical abstractions and the new abstract spatial moves of deconstructivism are congenial to the new socio-economic patterns of post-Fordism. The keywords that made this synergetic link-up possible were notions like complexity, self-organisation, network. The connection between architecture and Deleuzian philosophy was also made by Jeff Kipnis and Greg Lynn. I added the socio-economic dimension in terms of post-Fordism (which was also suggested by David Harvey at the time). Lynn brought complexity science and new biology into the mix, and I was inspired by the post-Fordism debate to explore the proliferating literature on new management and organisation theory. Here I found even more concretely applicable congeniality between the latest conceptions in corporate organisation (network organisation, self-organisation, fluid and blurred boundaries between domains of competency, etc.) on the one hand, and the latest repertoires of complex, layered and fluid spatial organisation of our (and our friends’) architecture on the other. I made this congeniality the basis of our first three-year AADRL research programme, Corporate Fields, which was — at least in my version — inspired by what I considered post-Fordism’s progressive, emancipatory economic and political potential. At that time, I saw the capitalist and neoliberal framing of these processes as a contradiction that could be bracketed and would eventually be overcome by a new left progressive politics (‘radical democracy’) that was left vague in the Marxist outlook I was still committed to. The demise of Eastern Bloc ‘communism’ did not shake my commitment.

However, my commitment to Marxism was slowly undermined by new theoretical influences. My interest in sociology in general, and in business organisation theory in particular, had led me to the work of Niklas Luhmann. I was digging into his huge, compelling oeuvre, reading nearly nothing else for years, and it slowly but surely weaned me away from Marxism. His work re-founds sociology on the basis of complexity and communication theory. His comprehensive system was the first theoretical social theory edifice that seemed able to compete with Marxism in terms of scope and theoretical ambition. As a mammoth single author’s work (which at the time was still ongoing), it was both more unified and more updated than what Marxism had to offer. Luhmann’s system too was a true ‘super-theory’, with the additional advantage that he reflected this fact explicitly. He did not espouse any explicit politics. His implicit politics were ambiguous, perhaps nihilist in their dry, sceptical tone, but certainly not socialist. My Marxist dream of mankind’s potential for democratic ‘self-consciousness’ faded in the face of Luhmann’s theory of a functionally differentiated society where incommensurable, self-referentially enclosed (‘autopoietic’) subsystems (economy, law, politics, science, etc.) coevolve without any overarching control centre or integral rationality, and where productivity gains are due to the adaptive information processing power of this de-centred system.

The political system was just one of many parallel systems that in no way could deliver decisive control over total social evolution. Any such attempt would break at the complexity barrier presented by the inter-relationships of contemporary world society. Successful attempts at control could only result in a regressive (totalitarian) blunting of society’s complexity. Under Luhmann’s influence my political ambitions faded altogether and my political economy outlook became, by default, rather mainstream, with increasing sympathies for market solutions over political solutions. Since the late 1990s I have built my theory of architecture on top of Luhmann’s theory of society, treating architecture as one of society’s autopoietic function systems.

Luhmann’s theory of coevolving autopoietic societal subsystems (function systems) suggests that it should be possible to find — in each epoch of society’s overall evolution — complementarities between the architectural subsystem on the one hand and the economic and political subsystems on the other. In short, it should be possible to align the styles of architecture with the stages of capitalism, and thus to ground the familiar stages of architectural history with reference to the stages of society’s historical evolution. As society’s political economy evolved through the various stages of capitalism — early capitalism, absolutist mercantilism, laissez-faire capitalism, Fordist state capitalism — the discipline of architecture coevolved via a sequence of epochal styles that roughly align with the above stages of capitalism: Renaissance, Baroque, historicism, modernism. The onset of the current stage of neoliberal post-Fordism spelled the demise of modernism and spawned a flurry of diverging architectural responses: postmodernism, neo-historicism, deconstructivism, minimalism, parametricism. It is my contention that parametricism is architecture’s most congenial answer to post-Fordism.

I had this theory all worked out in elaborate detail when in 2008 I was jolted out of my mainstream political-economy slumber by the financial crisis. What had I missed? What could explain this unexpected devastation? I looked around for explanations. I was already sufficiently sceptical about Marxist and left-leaning accounts that saw nothing but capitalism’s inherently contradictory and self-destructive tendency at work, unleashed by the neoliberal deregulation of recent decades. I looked around for alternative accounts and came across Austrian economics, initially via figures like Thomas Woods (Meltdown) and Peter Schiff (The Real Crash). I rapidly dug deeper and got hooked on the work of Ludwig von Mises, and then his students Friedrich von Hayek and Murray Rothbard. I had come across Mises before, in 1987 in Marxist circles debating the prospects of ‘market socialism’; I was fascinated by his polemic radicalism, but failed to see his significance. This time around I got hooked and invested a lot of time and energy to explore his monumental work. I got more and more radicalised and was soon ready for Rothbard’s anarcho-capitalism.

The political ideology and programme of anarcho-capitalism envisages the radicalisation of the neoliberal roll-back of the state. As a special form of anarchism based on private property as society’s most basic institution, its call for the extension of entrepreneurial freedom and competitive market rationality pushes to the point where the scope for private enterprise is all-encompassing and leaves no space for state action whatsoever, positing the privatisation of everything, including cities with all their infrastructures, public spaces, streets and urban management systems. Even the provision of the legal system can be imagined fully privatised, via markets with competing jurisdictions, multiple competing sets of statutes, competing private courts, etc. These are, intellectually, incredibly stimulating propositions and the rapidly growing literature around such libertarian themes is rather sophisticated.

So, my old presumption that all intellectual sophistication resides left-of-centre was more and more revealed to be an abject fallacy. In any case, the left-right distinction cannot at all capture (and orient us in) the contemporary political landscape and should be scrapped and replaced by a more appropriate compass.

Like the anarcho-capitalists, I have lost faith in ‘real existing’ representative-democracy and its centralised decision making which fails in its promises and is bound to fail more and more in the face of global interconnectedness. The scope for majoritarian dictates must shrink. Democracy can no longer cope with contemporary complexities — even if elected officials had the most selfless and noble of intentions. Contemporary society is probably better off betting on decentralised decision-making and an unleashed entrepreneurial creativity — a system where new products, services or institutions can be tried out and weeded out right away without first having to convince the majority. There should be no imposition of one-size-fits-all constraints on free contracting. One-size-fits-all schemas are an anachronism in contradiction with post-Fordism.

The disadvantages of state regulated capitalism and the potential advantages of a radicalised anarcho-capitalism are much more pronounced now — in the era of a computationally empowered post-Fordist network society — than they were during the era of Fordism, i.e. the era of mechanical mass production. Socialism — a centrally planned economy with a strong commitment to income equality — was to some extent compatible with the utilisation of the opportunities of mechanical mass production. But it is incompatible with the full utilisation of contemporary post-Fordist opportunities which require much more dynamic and intricate forms of social cooperation. This assessment is coherent with both Luhmann’s and Hayek’s understanding of society and its modern history.

The philosophical and methodological underpinnings of Austrian political economy — bottom-up action theory and a non-reductive methodological individualism — are compatible with Luhmann’s approach and theory. Hayek and Luhmann especially are congenial with respect to the shared intellectual paradigm of complexity theory. They concur in their general emphasis on self-organisation, emergence, evolution, and information processing. In particular, they concur in the assertion that modern societies have evolved to a point where an insurmountable complexity barrier stands in the way of any attempt to rationally direct societal development via central political control, and that any such attempt implies a regressive blunting of society’s highly evolved complexity and information processing capacity, with detrimental consequences for prosperity. Thus freedom (mutation) and competition (selection) are the evolutionary mechanisms that need to be given space to operate.

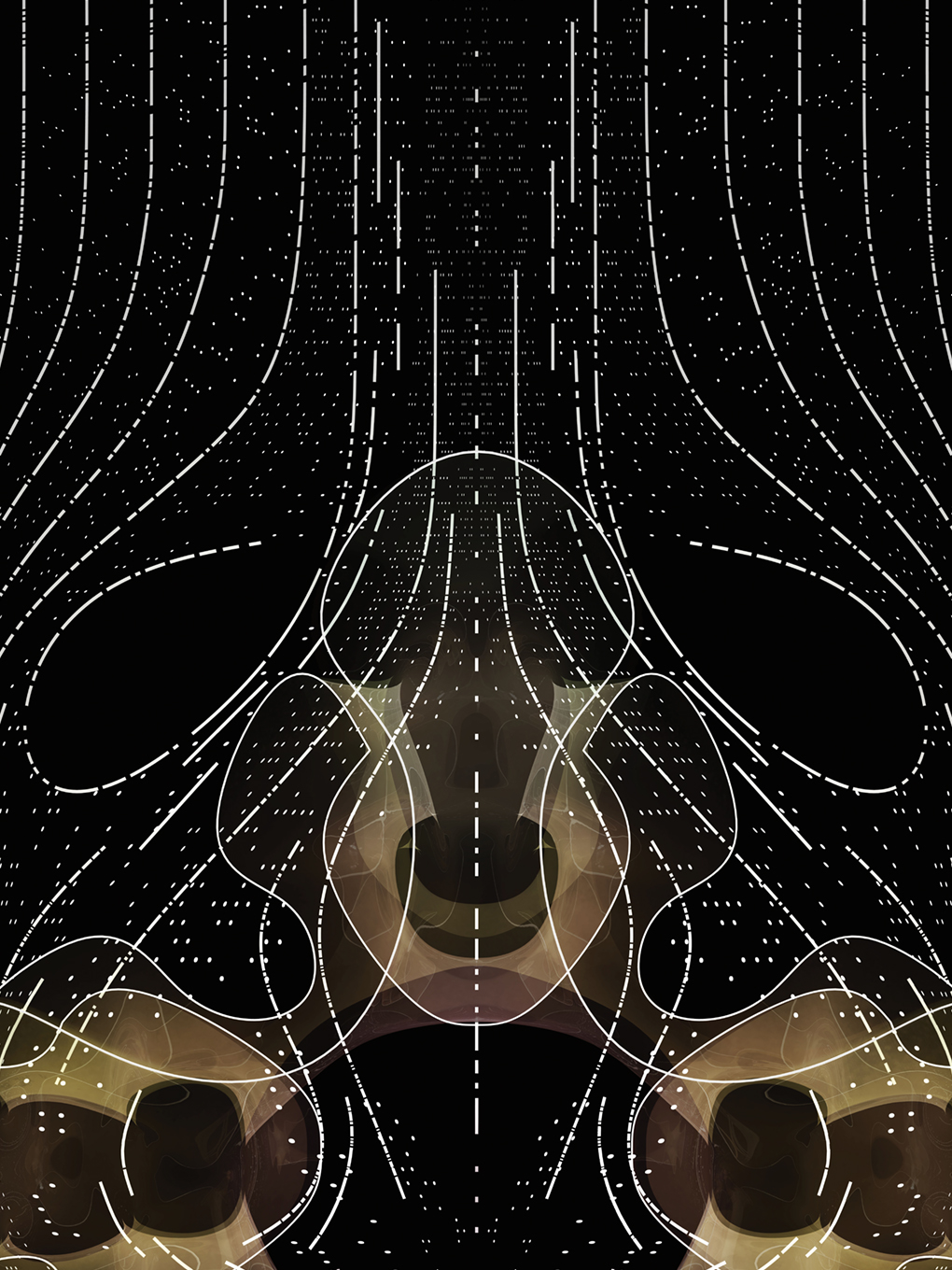

Zaha Hadid and Patrik Schumacher’s design for the Science Museum’s Mathematics Gallery, opening in December 2016. © Zaha Hadid Architects, used with permission.

Speaking of giving space, this might be a good moment to mention your involvement with Liberland, a libertarian micro-state established in on a contested piece of land between Croatia and Serbia. You are now leading the jury of an ongoing international design competition to find an urban framework for the nation-to-be — a ‘society that aspires to a maximum freedom’. What is the potential of Liberland, especially viewed in the context of the multiple crises currently wreaking havoc across Europe and the world at large?

I think Liberland is a fantastic effort on many levels. Vít Jedlicka [Liberland’s founder and current president] is a formidable force to be reckoned with. His project is as sophisticated as it is heroic. The chance that it might become real is only one of its merits. It is also a newsworthy, radical message and a tangible vehicle of political economy speculation which poses as many theoretical questions and conceptual challenges to us as it poses practical challenges. The project decisively poses the central challenge that urbanism faces in the current era of market-based urbanisation processes: to devise a methodology with many degrees of freedom; and abstract general heuristics allow piecemeal urban agglomeration processes that not only maximise programmatic synergies but make these synergies legible within an evolving navigable order.

The presence, or near presence, of a practical project has also always disciplined and guided the development of Marxist theory, although the blanket refusal of Marxists to ‘indulge’ in blueprints and detailed speculation about the prospects and probable (political and economic) problems of democratic socialism had been (and remains) its Achilles heel.

Avant-garde architectural speculation might attempt to extrapolate from current political realities via reference to advancing political trends and tendencies without collapsing into fruitless utopian speculation. This is what I am trying to do in my recent speculations about the prospects of an unleashed parametric urbanism under the auspices of a radical anarcho-capitalist societal order. It is of course a subjective judgment call to what extent this kind of speculation is fruitful. In my judgment such speculations are pertinent not only if the realisation of anarcho-capitalism is a realistic prospect, but due to the fact that it extrapolates current tendencies and is thus informative even for current conditions or more modest movements in the hypothesised direction.

In contrast to leftist inspired architectural speculations that imagine the reversal of the process of market liberalisation of recent decades, harking back to the 1970s, an anarcho-capitalist inspired architectural speculation radicalises manifest tendencies. I would argue that this is not only more realistic but also potentially a more fertile engine of architectural invention because it allows us to project into uncharted territory. The architectural competition for Liberland offers a stimulating opportunity in this respect.

However, while such speculative design research is both politically and architecturally stimulating, the primary task I have set for myself for the time being is to push parametricism into the mainstream, within the current political context, a task that is as eminently feasible as it is increasingly urgent for the thriving of our urban civilisation.

I assume by ‘speculations imagining the reversal of market liberalisation’ you refer largely to the work and influence of Pier Vittorio Aureli, both in academia and through his office Dogma (with Martino Tattara). As far as you reside from each other on both a political and architectural spectrum, you share a commitment to architecture itself, unlike the work that is touted as architecture’s current vanguard. For example, in , Assemble was given the Turner Prize and Alejandro Aravena the Pritzker, architecture’s most prestigious award, in addition to being appointed as the head curator of the upcoming Venice Biennale for Architecture. Aravena’s ‘urban do tank’ Elemental is known for its participatory design practices; the theme and title of the biennale is Reporting from the Front. In the wake of these announcements, you announced the ‘PC takeover of architecture is complete’, continuing a line of critique that you also raised in connection to the recent Chicago Architecture Biennial that highlighted a number of ‘socially engaged’ architectural projects and practices. Could you expand on this? Instead of radicalising, extrapolating or resisting current conditions, are architecture’s — or rather that of its supposed front line’s — ambitions confined within those of Big Society?

With your questions you poke into a most treacherous hornets’ nest, but we have to poke and stir it!

Pier Vittorio Aureli is only one of so many in architecture who argue from anti-capitalist premises as if from an unquestionable intellectual or moral high ground. Unfortunately, this anti-capitalist bias is dominant especially in the intellectually ambitious segments of our discipline. However, I respect Pier Vittorio, not because I share a commitment to ‘architecture-in-itself’ — I do not — but because I respect that he is a designing architect that teaches design on the basis of a theoretical position that encompasses both an account of society and a conception of architecture’s role within it. While his conceptions are fallacious, his practice has at least the right kind of ingredients required for an ambitious architectural practice. So I appreciate his ambition, although I consider the specific ingredients he is wedded to and the results he cooks up to be widely off the mark. I also respect that his teaching is still committed to building design when so many of our teaching colleagues defect to observation and ‘political’ debate, leading at best to ‘artistic’ or ‘conceptual’ provocations.

All the things you allude to in your question point to a problematic politicisation of architecture. This would not per se be detrimental if it did not threaten to swamp and usurp most of architecture’s discursive arenas. Another problem is the PC tilt of this politicisation where everything leads to the safe consensus around well-rehearsed humanitarian concerns. This not only flattens and trivialises our discourse but does so with a moralising force that makes it hard to escape this normalisation.

Again, politicisation is not per se negative. It could be energising. The historical background for the increasing politicisation of our discipline is twofold: firstly, we have been witnessing a long-term secular politicisation of all aspects of society, in the context of an ever-increasing capacity for society-wide communication; secondly, we are witnessing a marked acceleration of society’s politicisation since the 2008 financial crisis, the ensuing great recession, and the European sovereign debt crisis, events which re-politicised myself as much as everybody else. These events had various political repercussions, like the Occupy movement, the ‘Arab spring’, and the upheavals in Europe’s political landscape in reaction to controversial austerity programs.

In this historical context, the politicisation of our discipline must be seen as a perhaps inevitable moment in the politicisation of all aspects and domains of societal life, implying that any further attempt to deny, resist or repudiate this is futile. However, what we must not accept as inevitable is the pretentious dilettante quality of this debate, its PC tilt, and its consequently regressive nature. We must repudiate the all-too-often automatic anti-capitalist and anti-business bias that informs most contributions to the politicised architectural discourse. Even if the politicisation of our discipline has progressed to a point where political engagement becomes inevitable, there must remain a space for an architectural discourse that discusses and evaluates the best architectural solutions to societal requirements as they are posed today under current political and societal conditions, however questionable they might seem from certain political perspectives.

In particular, we must not allow the most effective contribution and the proper purposes of our discipline to be diverted by ‘urgent’ or ‘humanitarian’ issues that seem to trump all other issues due to moral urgency. This is self-destructive populism and as irrational as it would be to send brain surgeons or medical researchers at the frontier of medical science to Africa to distribute urgently needed standard medication.

What can we expect of Aravena’s biennale? I am afraid it will continue the unfortunate trend of previous biennales — inclusive of the recent, inaugural Chicago Architecture Biennial — to thematise weighty political and moral issues (like poverty or ‘the global housing crisis’) and to validate (via its prizes) polemical gestures or documentary engagements with such issues as more important and interesting than the most sophisticated contemporary architectural design achievements at the technological and programmatic frontier of innovation.

I am not saying architectural excellence is in itself a value and that societal concerns do not matter for good architecture. Quite the contrary: I am insisting that architectural theory and thus practice must start with the clarification of architecture’s societal function, i.e. with a clear understanding of the built environment’s significance for social processes and of architecture’s specific role with respect to the progressive development of the built environment. I am indeed arguing that parametricism has to shift its discursive emphasis from technical to social functionality and explicitly demonstrate how its methodology and repertoire are geared up to address the requirements of contemporary social dynamics and institutions.

However, to address architecture’s societal function — the innovative spatio-morphological ordering of social interactions in increasingly dense and complex scenarios — the discipline and its most ambitious protagonists have to be cognisant of where the frontier of innovative design research is located, i.e. where the investment of discursive and design research efforts would be most important and productive. In my view, this can only be with respect to the new challenges posed in the most advanced, high value arenas of our world where unprecedented conditions — the new level of density, diversity, complexity, interconnectedness and dynamism in our most productive social institutions — call for original innovations that must draw on the most sophisticated methodologies and computationally advanced design processes. In contrast, the alleviation of issues like the poverty-induced lack of provision of well-established housing standards does not call on the most advanced capacities of the discipline and profession, nor indeed does such an issue even lie within the reach of architectural professionals’ powers.

We need to be strategic with respect to where and how we can best employ and leverage our specific disciplinary intelligence. Again, importantly, this position stands independently from my political hopes and recommendations, and in my perspective, parametricism remains architecture’s best bet under current political conditions, just as it would remain its best bet under a more libertarian political economy. I believe parametricism is indeed congenial with radical anarcho-capitalism which, in turn, I consider to be our best political bet. But I do not want to politically taint or tie up parametricism by giving the impression that it has a necessary, radical political bias. The function systems of world society coevolve and influence each other without necessary connections or inevitabilities.

My ambition is to innovate my discipline and lead adaptive efforts with respect to the conditions and opportunities of post-Fordist network society. This adaptation must be based on current social, economic and political conditions, and can only risk to speculate moderately forward along salient tendencies.

Martti Kalliala is an architect whose work focuses on the identification and conceptualisation of emerging spatial conditions. He recently curated the symposium Ultimate Exit in collaboration with the Van Alen Institute in New York, and presents his new installation PatchWork as part of the 2016 Oslo Architecture Triennale. He is the editor and co-author of Finland: The Welfare Game, and is a regular contributor to Harvard Design Magazine, Flash Art and other journals.

Header image: Zaha Hadid and Patrik Schumacher’s design for the Science Museum’s Mathematics Gallery, opening in December 2016. © Zaha Hadid Architects, used with permission.