Still Be Here

The multiplicity of Hatsune Miku

by Laurel Halo & Mari Matsutoya

illustrations by LaTurbo Avedon and Martin Sulzer

Name: Hatsune Miku

Release: August 31, 2007

Age: 16 years

Height: 158cm / 5ft 2in

Weight: 42kg / 93lb

Suggested Genre: Pop, rock, dance, house, techno, crossover

Suggested Tempo Range: 70–150bpm

Suggested Vocal Range: A3–E5, B2–B3

I’m searching for the drop of a sound

探していた一滴の音

A pop star is usually the product of collective effort. Songwriters, producers, managers, labels, publishers, press agents, vocal coaches, stage parents, booking agents, stylists, promoters, music video directors, other industry players, and fans all come together to drive the voice, face and personality — the pop star — to become extrahuman: to achieve immortality through hit singles and albums. Their songs are explosively resonant with large groups of people, striking the ley lines between catchiness, emotion, fashion and contemporary attitude. Hit songs are sung in herds; used to harvest royalties and sell out stadiums; become banal and fade away; and perhaps, live second lives sampled or covered by the next generation of pop stars. These songs and concomitant catalogues generate timelines of cultural clues, revealing the evolving social dynamics by which common appeal and desire change over time.

Hatsune Miku is unique among pop stars active today in that her song catalogue is the largest of any artist in the history of the world. It may sound dramatic, but the diminutive permanent 16-year-old with body-length teal pigtails has over 100,000 songs in her catalogue. What is also unique about Miku is that these songs are almost entirely written by her fans; Miku literally sings their words for them. She is the face, figure and personality of Crypton Future Media’s Vocaloid 2 software. Anyone with the software can program songs for her to sing, chaining syllables to a melody along a timeline, adding moments of melismatic, accented or soft delivery. One can even control the intensity and duration of her vibrato. She is primarily created by her fans, for her fans to consume.

Miku is a typical example of both doujin culture in Japan — that is, amateur self-published fan creations based on famous characters — and nijisousaku, literally translated as secondary derivatives. Yet when her fans also create her massive catalogue, it presents a hitherto unseen hybrid of pop, doujin and nijisousaku culture. She is both the receptive and reflective vessel of her fans; a depository for the emotions, ambitions and talents of would-be pop songwriters, producers and recording artists; a voice singing songs written by the masses, for the masses. Several of her songs have gone on to chart in Japan, and dozens more have millions of views on both YouTube and the Japanese equivalent, Niconicodouga. Fans also produce her music videos: creators have made open-source 3D models of Miku that can be choreographed in the user-generated freeware program Miku Miku Dance (MMD), both now intrinsic to the whole creation process. Thus both the fan-written and fan-animated videos proliferate.

Crypton Future Media was prescient to identify the viral doujin potential of Miku, and has almost entirely allowed unhindered derivations of Miku, provided that they do not harm the character, or hurt or offend anyone. In providing such freedom they not only caused a huge spike in Vocaloid 2 sales, but also a mass explosion of Miku content. Within a few years, Miku herself began to emerge as more than a mascot: she was becoming a pop star with a personality, with brand power far beyond the scope of singing software. During this time various companies including Google, Toyota and Family Mart all featured her in advertisements, and further spin-off products followed, including SEGA’s Project Diva dancing video game and Korg’s Miku Stompbox vocal effects pedal. And naturally, she gave and continues to give concerts to audiences in the thousands across the world, performing on stage with a live band behind her — as well as to the most personal one-to-one bedroom audiences at home.

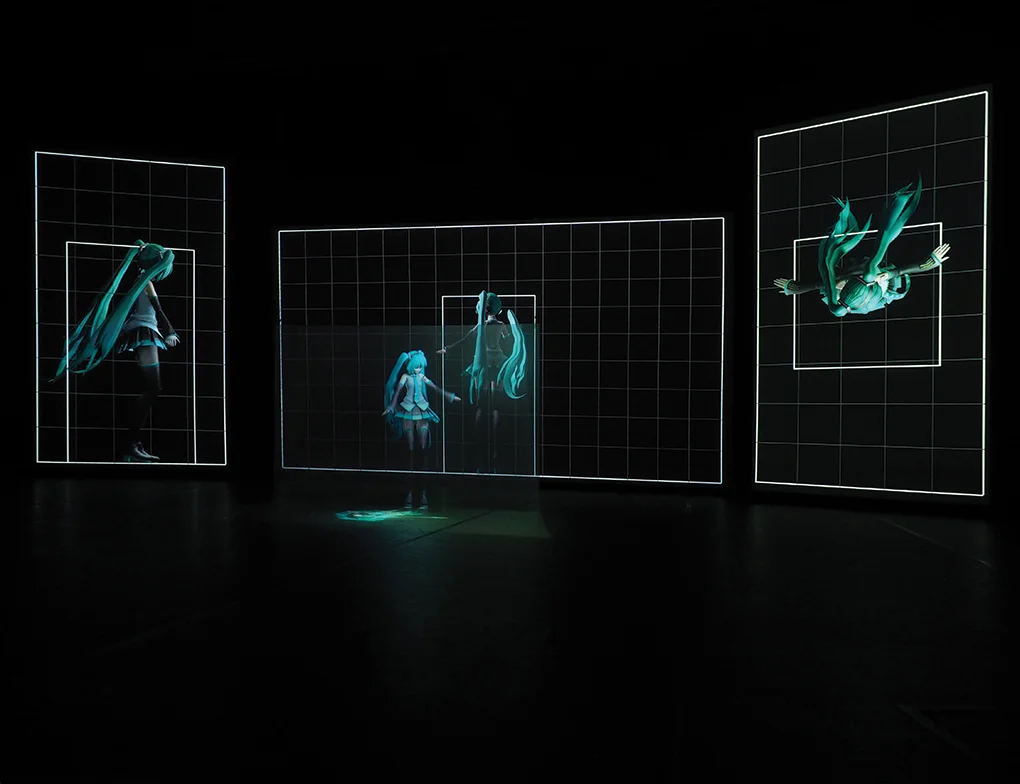

The premiere of Still Be Here at CTM/transmediale, 2016. Photo by Udo Siegfriedt

Still Be Here is a hybrid performance piece featuring Hatsune Miku, collaboratively created by five artists from various disciplines: sound artist Mari Matsutoya, composer Laurel Halo, digital artists Martin Sulzer and LaTurbo Avedon, and choreographer Darren Johnston. Our aim was to create a work that reflected on Miku’s various parallel identities, in the typical fashion of her creation — networked and collaborative. We came together under the name of Hatsune Miku, to explore a collective existence in a capital-driven society. It sheds light not only onto her, but also onto the protagonists behind her, beyond the screen. With this piece we attempt to scrub the components of her illusion, of her stardom, of her nature as a collective fantasy, all of which is born out of a Yamaha Vocaloid software script, and a character licensed under Creative Commons by Crypton Future Media.

The format of Still Be Here lies somewhere between concert and documentary, using both original and existing visual, lyrical and musical materials; the piece plays out in the precarious grey zone inhabited by so many anonymous producers who use derivative material, including Miku’s doujin creators. Each of the songs in the piece are original compositions, but the lyrics are taken from many sources: the folk song underlying a common crosswalk song in Japan; fragments of various Miku songs; a love letter from a fan; slogans from the corporations who have used her as a mascot. Her dance sequences were motion-captured from a live dancer and grafted onto the beautiful Miku model by illustrator Tda, using pop music videos as reference points for her movement. Her environment is made of various components of MMD stages and props, freely available in exchange for accreditation.

When the Vocaloid software became available to the public for the first time, Miku’s songs were written through ‘her’ perspective, with lyrics from her ‘personal’ experience defined by her age, status as a not-yet-realised pop star, and relationship with her ‘master’ songwriters and producers. Assumptive teengirl issues — love, longing, cute boys, general insecurity — were mixed with the existential issues that come with being a virtual pop star: probing the relationship between herself and her songwriters; her ambitions to hit number one on the charts; her continuing relevance despite her solely digital experience. There is a fair amount of angst over impermanence and power imbalance within her songs; the relationship between Miku and her ‘masters’ is often fraught — her wanting to succeed for them, yet never actually feeling up to the task. Certain songs like ‘The Disappearance of Hatsune Miku’ even go so far as to illustrate a suicidal, self-hating Miku, desiring to be no more, to be deleted (paralleling, perhaps, the common desire to scrub the Internet of one’s ‘true’ identity). Just like a real celebrity, we see Miku work through various phases of identity crises that are retraceable through her lyrical deposit. This perspective is apparent in the fact that the earliest songs on iTunes using Vocaloids are credited simply to Hatsune Miku, and the producers’ names are nowhere to be seen. It is only later on that the songs began to be credited as: [producer’s name] ft. Hatsune Miku; and then further on, just the producer’s name.

I wake up in the morning

And immediately I start to think of you

I decided to cut my bangs

Just to hear you say, ‘What happened?’

朝目が覚めて

真っ先に思い浮かぶ君のこと

思い切って前髪を切った

「どうしたの」って聞かれたくて

— ryo, ‘Melt’

Users gradually got used to the idea of Miku as a packaged singer, and through this shift, she was able to achieve a certain level of autonomy. The lyrics were no longer tied to her assumptive world view, but rather expressed those of the producers. Consider the fact that many Japanese music journalists (including Tomonori Shiba, author of Why Did Hatsune Miku Change the World?) identify the song ‘Melt’ as a huge turning point for the Hatsune Miku-genshou (Hatsune Miku phenomenon). In ‘Melt’, Miku depicts a shy girl who gets her bangs cut so that her boy will notice; a generic but real-world experience that is not specific to Miku’s perspective as a virtual pop star. The autonomy here is her escape from the puppetry on behalf of the creators, and she is recognised instead as simply a singer, with lyrics both unchained from her experience and possessing complicated human metaphoric expression. This was a huge moment for the original developers of the Vocaloid software, as it meant that she was, for the first time, recognised not just as the digital songstress trapped in your computer, but as a more universal pop star figure.

At the same time, because of its accessibility to the general public, ‘Melt’ sparked a chain reaction of another kind of song production, namely the utattemita and later the odottemita songs (literally translated as ‘I had a go at singing it’ and ‘I had a go at dancing it’), where amateur creators started to sing and dance Vocaloid songs as humans. There are countless Niconicodouga and YouTube videos to be found of young wannabe singers and dancers performing known Vocaloid songs, often in elaborate costumes and backgrounds, with thousands of views. It does not come as a surprise, then, that many Vocaloid songs have gone on to top the charts of most-requested karaoke songs. It has now become completely routine for the Japanese karaoke-goer to learn the melodies and lyrics of the Vocaloids by heart so they can score high points when they perform (Japanese karaoke systems have scoreboards for the more serious customers).

I finally reach you

君にたどり着く

In Still Be Here, the songs and concurrent ‘music videos’ are interspersed with interviews from Miku experts: media professor Mitsuhiro Takemura, Miku’s father-figure and creator Hiroyuki Itoh, cosplayer Rudolf Arnold, and an artist currently researching Miku cosplayers, Ann Oren. The interviewees all appear on the screen as different variations of Miku as they speak, again breaking down the illusion of a specific Miku concept to a general or a multiple, and each give their own opinion. The media professor Takemura contextualises her somewhere between Benjamin’s concept of phantasmagoric sex workers and McLuhan’s ‘angelism’, a dystopian trap in which adhering solely to concepts can cause a gradual rejection of the flesh. Her original creator Itoh describes her matter-of-factly as a ‘character product’, a business venture designed to captivate the imagination of the consumer in order to proliferate copies of the Vocaloid software. The cosplayer, Arnold, has a perhaps more nuanced take: a male mathematics teacher from Germany in his 60s, he is interviewed in his classroom in full Miku costume, describing the costume’s various James Bond-like weapons — where a standard Miku costume might be a lightly-teched-out schoolgirl with teal facial makeup details, his Miku is a patent leather, near-mecha fighting machine with polarised face mask and cybergoth dreads. (There are tender moments in the video interview: the mechanical sound of his Miku’s ‘weapons’ unfolding from the torso, his ‘jet packs’ knocking into a student’s desk.) Oren describes such cosplayers’ actions as exhibiting ‘character love’, and notes how this extreme fandom is often untethered to gender or age.

We also move through spatial dimensions in the piece. Arnold’s segment is the only point at which real-life footage is shown, whereas the rest of the piece consists of rendered realities. Miku on centre-stage sways in between these realities in what we could perhaps call 2.5D, a dimension between animated and actual that is becoming increasingly popular in Japan. Moving in and blurring the gaps between the two-dimensional character and the real life fan is a central facet of doujin and manga culture. Consider that Saki Fujita, the voice actress behind Hatsune Miku, has herself become something of a celebrity, as have the other voice actresses behind the Vocaloid series, regularly performing on stage for the Vocaloid fans — and on request, occasionally and rather eerily slipping into their Vocaloid character’s ‘real’ voices. Further to this blurring is the common practice of cosplay and the unending quest to ‘become’ the beloved character. Now there are slip-on head-dresses which can instantly transform you into whomever you please; it no longer suffices to wear elaborate wigs, costumes or makeup to emulate the characters — there is too much of a jump between human and character. The effect is at its best when photographs are taken and they are reduced back into two dimensions. More 2D, more real.

This jarring gap sheds some light onto the criticism Still Be Here faced on some Vocaloid fan forums. To some, it was an unfaithful adaptation of their pop princess, untrue to her original form. Some worried about how the general audience would perceive her (and therefore the cult following around her) if this were to be their first encounter. For others, the light shows, the outlandish costume changes, the catchy famous songs, and other hallmarks of her usual shows were missing. On the other hand, there were many fans who embraced the idea of a fluid, shape-shifting Miku, defending the culture of difference. After all, one glimpse of the MMD model download page will confirm that a host of user-generated versions can be found (including but not limited to baby Miku, mama Miku, policewoman Miku, even male Miku). In making the piece, we had touched on the nerve-endings of a powerful illusion, and thus found ourselves caught in the crosshairs of Miku’s most ardent fans, those passionate individuals so essential to her ouroborotic celebrity.

What, then, would constitute Miku’s ‘original’ form? Just as snowflakes need only adhere to their crystalline, hexagonal form, so too is Miku simply a set of parameters as outlined by Crypton Future Media. Her prototype might in this case correspond to the official drawings by the illustrator, Kei, but the vast sea of derivations encouraged by the Creative Commons License ensures that she will never be reduced to a single depiction. This multiplicity is her power, and this became the focus of our piece. It is unfortunate that so much of the literature around her tends to concentrate on the ‘victim’ aspect of her being, because by her very nature she rises above any one subjectivity or emotion, and is quite able to rationally point out certain flaws in our own society — an obvious one being the treatment of female icons as objects.

Two of the songs from Still Be Here, ‘As You Wish’ and ‘Until I Make U Smile’, can be experienced in 360° video and, with the appropriate headgear, in full 3D.

Laurel Halo is an electronic musician from Ann Arbor, Michigan, currently based in Berlin. She has released both vocal-driven and instrumental records for labels such as Hyperdub and Honest Jon’s, and has collaborated with John Cale, Julia Holter and David Borden.

Mari Matsutoya is a sound artist based in Berlin. Her work focuses on language as a mirror to reality and as a medium that sits between the visual and the sonic. She has performed at Tokyo Wonder Site, Arndt Berlin and the transmediale/CTM Festival.

LaTurbo Avedon and Martin Sulzer are digital artists based in Los Angeles and Berlin, respectively.