An Atlas of Fiducial Architecture

A tour through the shadows of the digital

by Liam Young

photographs by Google Earth and DigitalGlobe

DigitalGlobe’s WorldView-3 satellite, built by Ball Aerospace, is one of the Earth-scanning satellites used by Google Earth. Photo © Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp.

Hurtling above us at almost 7,000 miles per hour is an utterly improbable creation. Delicately dancing with gravity is the Google Earth satellite looking down at the planet and tiling together a digital map of its surface. At the resolution of these images a pixel is less than half a metre in scale, just a bit bigger than the width of our bodies. Ancient craftsmen once measured the world using parts of the human body, the cubit, based on an elbow, an inch, the length of a thumb. The seminal modernist architect Le Corbusier designed his buildings based around his ‘modular’ — a new system of measurement that he generated from the anthropomorphic proportions of our bodies. We once understood our world through systems that put the human, our own vision and patterns of occupation, at the centre of the structures that we design. In a culture of the digital, however, the body is no longer the dominant measure of space, it is the technologies through which we see and experience the world that now define how we make it. In this context we must begin to imagine new design sensibilities that can resonate across both human and machinic experience.

In intelligent machine vision systems, a ‘fiducial’ is a recognisable marker placed in the environment which is used for calibration and navigation. As the pixel is now defining a new ‘modular’ we are seeing the emergence of a new genre of architecture, a kind of ‘fiducial architecture’, or a post-human architecture designed to be read by machines but that finds its site both in the digital spaces of the network and also in the physical ground of the earth. In the eyes of the computer such an architecture is reimagined as a marker for computer calibration, encoded with digital information, or a locative point on which to anchor a luminous AR structure of intricate detail, immeasurable complexity and animated pixel assemblies.

We can take a tour across this digital skin of the earth, visiting sites and structures made for and by machines but strangely suggestive of these alternative forms of spatial experience. We can trace their edges, glitches and anomalies and see where the digital bubbles to the surface to condense into an atlas of fiducial territories, landscapes and architectures. A cartography of structures scattered along a trajectory from the screen to the shadows they cast across the planet.

Sandy Island, New Caledonia

19° 13′ 12″ S, 159° 55′ 48″ E

Travelling across the pixel sea of Google Earth, we wash up on the shores of Sandy Island, just off the coast of Australia. Sandy Island is a collection of dark pixels, GPS coordinates, hyperlinks and stories. Originally charted by the whaling ship Velocity in 1876, the island has long been an ‘evidence doubtful’ landmass, a place perhaps originally recorded to be a trap to support a map’s copyright, or a mislabelled pile of volcanically ejected pumice that was seen drifting on the horizon. This cartographic apparition remained visible in Google Earth until an Australian research vessel confirmed its nonexistence during a 2012 expedition to survey the ocean floor. Up until that point, to a world of Google explorers and hyperlink adventurers, Sandy Island was just as real as any other place they visited online. If places and spaces exist in the mediums through which we experience them then they become just as real as any other. We can design in these digital landscapes, conjuring architectures of code, GPS tags and metadata, to be read and disseminated by machines, experienced and inhabited by us.

Port of Hong Kong, Victoria Harbour

22° 20′ 03″ N, 114° 06′ 59″ E

Drifting within this sea of GPS islands is the computer-controlled container fleet of the mega-shipping industry. The paper sea charts and maps once scribbled over by captains have now been sucked into the screen, and the ships now navigate autonomously based on traffic algorithms, efficient route processing and satellite positioning. To these digital captains any feature that appears on its screen is just as real as anything in the water. When the ships dock they are met by portside cranes that are also driven by these same company algorithms. A ship used to moor in port for weeks whilst every object, crate and barrel was carried on board by hand. Now, autonomous creatures roll across the tarmac surfaces of markings and painted lines, their operators just passengers in the machine, their bodies repurposed as a component in the landscape-scaled robot that stacks the containers ready for delivery.

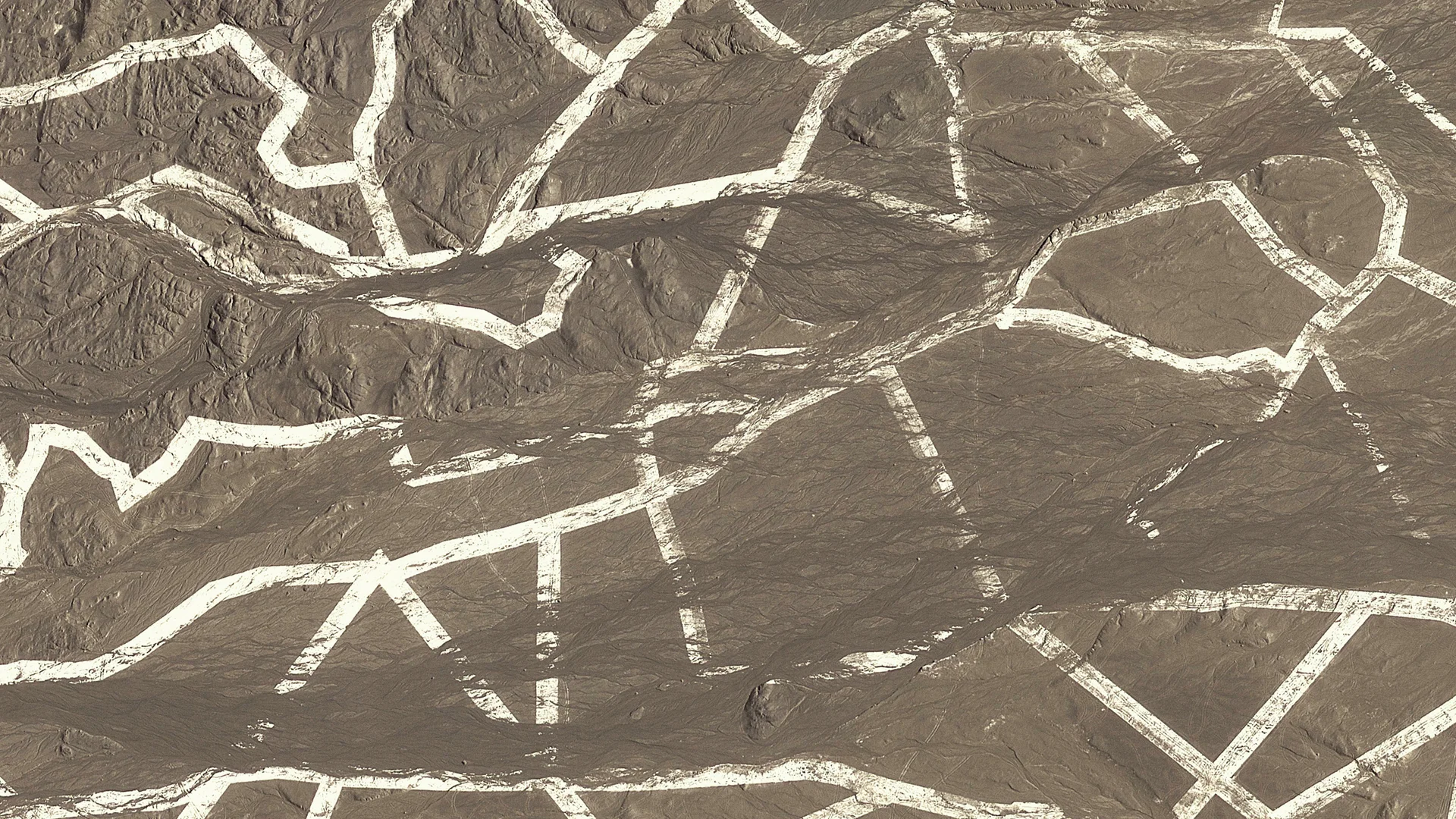

Satellite Calibration Target, Gobi Desert

40° 27′ 08″ N, 93° 44′ 32″ E

Deep in the Mongolian desert, huge landscape-scaled fiducial markings are focused on by the same machines watching over the container ships. Not evidence of some ancient culture, or forgotten versions of the Nazca lines, they are the traces of the new tribes of the digital: the animal tracks of orbiting machines. This is a satellite calibration target, a machine-vision graphic etched into the earth and supporting the precision this whole system relies on. These patterns were created to give aircraft and satellite-mounted cameras something on which to calibrate their lenses, allowing them to test resolution and their ability to take clear pictures at high speeds. The surface of the earth is a digital test pattern, as our landscape is scored with the traces of a new kind of autonomous aerial infrastructure.

Pinewood Film Studios, Buckinghamshire

51° 32′ 53″ N, 0° 32′ 05″ W

When a machine system is properly calibrated and understands its position in physical space the digital can be collocated with our own physical experience. This is the commodity of the film studio, where physical emptiness is the critical asset — spaces designed to be as open as possible to reimaging, so that the same space can be, for one week, a hellish landscape on an alien planet, and the next, a rainy New York street ready for the last kiss of a ditzy rom-com. Onto these blank spaces, stage sets of pixels are projected. Behind the film fantasy they are just green-screen structures adorned with crosshairs, calibration markers and ping-pong-ball body suits. Modern film studios are a new kind of architecture, stripped back to become scaffolds and infrastructure for a digitally constructed world.

As augmented reality explodes the CG experience from the cinema screen to the city street, an emerging form of architectural ornament is beginning to be defined by machine vision and camera tracking algorithms. This will be the physical world left behind when everything disappears into the lens of Google Glass or Oculus Rift. When we turn off the bespoke billboards of Minority Report’s urban spaces — the tailored ads, navigational prompts, Tinder profiles and tracked status updates of our sci-fi cityscapes — we will see a world where everything has become a screen. An architecture that is lying in wait, ready for the premiere of a million animated movies that will illuminate its surfaces with colour, detail and specificity.

Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, Pripyat

51° 22′ 52″ N, 30° 07′ 02″ E

Once called ‘The City of Tomorrow’, the Chernobyl nuclear zone is now a seemingly abandoned post-human landscape. In March 2002, a group from GSC Game World travelled to the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Armed with cameras and sketchbooks they meticulously documented the landscape that would soon become the photorealistic environment of their video game S.T.A.L.K.E.R. Now, security guards here tell stories of their nights in the zone, as they chase S.T.A.L.K.E.R. fanboy gamers that break into the restricted city to re-enact their digital characters and plot lines. Pixels give way to radioactive particles as they wander the city, airsoft rifles over their shoulders, hand-stitched uniforms and surplus gas masks keeping out the toxic dust.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. has transformed this place into a hyperlink landscape, still and quiet but at the same time filled with a thousand footsteps and digital gun shots echoing from distant weapons. Here are two superimposed cities, like an urban moiré effect, constantly shifting between one world and the other. It is a mirror site, both its digital self and its physical self — a new type of city distributed across the planet into flickering constellations of luminous rectangles.

Amazon Fulfilment Centre, Swansea

51° 37′ 27″ N, 3° 51′ 46″ W

Stretching out before us in our Atlas are the endless shelves and storage bins of the Amazon Fulfilment Centre. When we send an order to Amazon this is where it goes. As the digital leaves the screen, its patterns and code restructure architectural spaces in ways it is difficult to comprehend. The Amazon bookshelves are stacked based on a complex sorting algorithm engineered around sales frequencies and complex buying patterns. The search terms and suggested readings lists of the web crystallise into unintelligible juxtapositions and calculated adjacencies. Amazon workers rush through the stacks, navigating from book to book, filling orders by following the most efficient route generated for them by the bespoke tablets they constantly carry. Through this interface they are able to make sense of this system; but it is not organised for them, it is a space organised by digital logics, and inhabited by their bodies repurposed as machines.

Our cities are starting to be organised by similar algorithms of big data efficiencies. Like the fulfilment centre, we can imagine emerging urban forms designed around satellite sightlines, or cities impossibly intricate and dense — we locate ourselves in space, not through sightlines and visual orientation points anymore but the pulsing blue dot of a live updating Google map.

Facebook Data Centre, Prineville

44° 17′ 45″ N, 120° 53′ 01″ W

Terms like ‘cloud’, ‘wifi’ and ‘web’ are suggestive of something omnipresent, ephemeral, everywhere and nowhere, yet these structures are supported by an extraordinary, planetary-scaled physical infrastructure. In Prineville, Oregon, a sleepy, unremarkable town, at the confluence of cheap hydro energy and tax incentives are the data servers of Facebook, Google and Apple. Every ‘like’, love letter and ironic update, every photo that’s been taken, every photo that ever will be taken, is stored in these purring machines. At a time when our collective history is digital, this is our generation’s great library, our cathedral, our cultural legacy.

Is the internet a place to visit, are they sites of pilgrimage, spaces of congregation to be inhabited like a church on Sundays? Would we ever want to go and meet our digital selves, to gaze across server racks and watch us winking back, in a million LEDs of Facebook blue? Every age has its iconic architectural typology. The dream commission was once the church, Modernism had the factory, and in the recent decade we had the ‘starchitect’ museum and gallery. Now we have the data centre.

Kalgoorlie Super Pit, Western Australia

30° 46′ 26″ S, 121° 30′ 00″ E

It is in the massive mining excavations, carved out of the wilds of outback Australia, that our new digital reality begins and ends its life. The material from this site, now one of the largest unnatural holes on the planet, is embedded in all the objects of technology we carry around with us now. With every tech gadget we buy, with every choice to upgrade, we dig a little deeper. The computer models of mines are now linked live to the fluctuations of metal prices on the stock market. It is a landscape of data geology. If gold is priced high, it becomes cost effective to mine lower concentrations of ore; if the price is low, the week’s excavation plans focus only on richer ground. Every modern mine site can be read as a kind of data visualisation etched into the earth at the scale of the Grand Canyon. As explosives, diggers and drills have replaced the slow erosion of rivers and earthquakes, we are scoring our economy into the archaeological record, a chronicle of the digital permutations that drive the modern world.

The infrastructures of the digital world have extraordinary implications on material experience. These are the architectures behind the screen, and beyond the fog of the cloud — the physical outputs of our digital engagement with the world. Architectural craft has long been defined by the means of production of the era. Artisanal stone masons once carved column capitals with the motifs of gods and nature, and Modernism abstracted surfaces to the prefab components made possible by factories. The Atlas of Fiducial Architectures is a journey through a catalogue of structures that suggest an emerging design language conditioned by these new forms of computation infrastructure. This collection of post-human architectures and spaces reverberate across multiple frequencies, across multiple forms of site and experience. An atlas to a world where the terms virtual and real no longer apply but where a luminous architecture can cast shadows across both the physical and digital spectrums.

Liam Young is an architect, lecturer and critic. He is co-founder of Tomorrows Thoughts Today, a London-based think tank exploring the consequences of fantastic, speculative and imaginary urbanisms. He is also co-founder of the Unknown Fields Division, a nomadic design research studio, and is a visiting professor at Princeton School of Architecture.